INTERVIEW WITH Roger Corman by Eric S. Eichelberger

We are proud to present for the 2004 Shock a go go film festival, Roger Corman (applause)

Roger Corman: I’m delighted to be here for Shock a go go and I hope you enjoyed The Raven and a bunch of other films. They were fun to make and I hope they were fun for you to see.

Eric: Mr. Corman, who and what started your long string of cameos in your director’s movies?

Roger: It started with Francis Coppola when he did Godfather Part II. He called me and asked me if I wanted to be on the set of the crime and investigating committee in the Godfather. I said, sure. And when I went there, we worked two days and it was very interesting. Everybody on the committee was either a writer, director or a producer who knew or was a friend of Francis’ and Francis took us to lunch the first day and I think it was Bill Bowers, a comedy writer said, “Francis, how did you choose us?” And he said he had been watching one of the senate investigative committees on television and he found that all of the senators looked very senatorial. We all drew ourselves up. They all spoke very intelligently and we drew ourselves up a little more and he said they were all a little awkward on camera. And I thought, that’s great casting. He understood that senators were on a certain level but at the same time they weren’t really actors. So if he got writers, directors, and producers he got people who at least knew something about what was going and could give a performance but would be a little bit awkward on camera because we were on the other side.

Eric: Roger, how did, I was interested in how some of your earlier films were reverted to public domain.

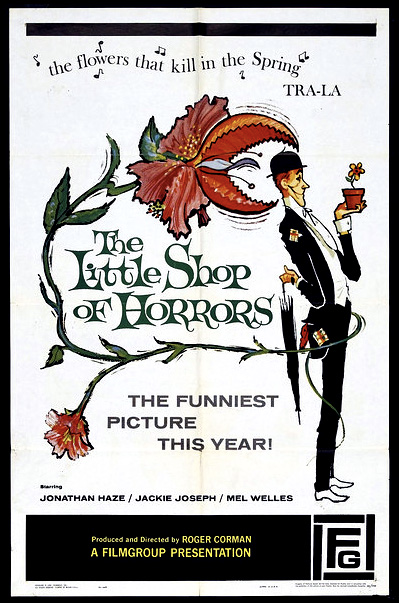

Roger: We were not that careful with the copyrights on some of the earlier films. And a couple of them got away from us. What it was, I was shooting a whole lot, I think one year I produced and directed eight or nine films in the year. It was something like that. We were going so fast that sometime the paperwork got away from us and some of the copyrights got away from us as well. I don’t know what to do about it. One of them was very strange. The Little Shop of Horrors – the copyright got away from us but Chuck Griffith, the screenwriter was very careful to copyright the script and of course I own the script having hired Chuck. So Chuck and I became sort of partners in his copyright of the script which gave us copyright protection of the film.

Eric: Do you have any advice for do-it-yourself filmmakers?

Roger: The first advice I would give is to get some preparation. If you can, go to a film school. Going to a film school, you learn the basic techniques. I had to learn, I went to engineering school. I learned on the job as did most of the people of my generation and of earlier generations. If you can, go to a film school. If you can’t, even one or two courses and extensions which costs very little money. UCLA and SC which are two of the best schools in the world have extension courses. And you can go in the evening and learn something. If not that, I think the thing you can do is get a camera, a digital camera and start shooting. There are various books you can buy. You can learn by reading the books and start learning so you understand the grammar of the film, how to set up the shots, how to edit, how to put a film together. Beyond that, the easiest way of course is if you can write a script which somebody will finance and that’s wonderful if you can do it. If not, you’re out there trying to raise money. On my first film, I had written a script and sold it. I took the money from the sale of the script and I raised a little bit more money and I gave percentage of the profits to most of the crew and the people working on it. So they got some pay. But they got a small amount of money with but they got the hope of profits. And there were profits. The picture was successful.

Eric: What about the Fantastic Four movie? Is there any time that possibly will be released?

Roger: It may be. Fantastic Four was one of the strangest experiences I was ever involved in. Bernd Eichinger, the German producer who had the rights, called me in September a number of years ago. And I came in and had lunch. And he explained his situation. He had an option on the rights and he had a thirty million dollar budget. And he didn’t have the thirty million dollars and the option was to expire on December 31st. And he asked me can you make a low budget picture. All you have to do is start shooting before December 31st so I can retain my offer. And I said let me send the script down to the guys at the studio and we’ll talk about budget which they did which was about a billion dollars. We had to cut a few things out but surprisingly not that many. And he said when do you want to start? I said give us all the time we want and we’ll start on December 31st. And he said, that will be so obvious to the people with the option and he said, let’s start on the 26th? And I said, Bernd, it’s going to be pretty obvious to anybody and we compromised on the 28th or the 29th. And the picture turned out pretty well. And he had a deal with me, I forgotten the details of it. But we were going to try to release it theatrically and he was going to put about five hundred thousand dollars in print and advertising and we were going to go regionally. And this was the time when low budget films were already being frozen out of theaters. Even though Fantastic Four is a known comic book title, the picture turned out rather nicely. It was five hundred thousand dollars. This would be a good experiment but he also had a clause that he could buy everything out for ninety days after we made the film and give me a very nice profit. And unfortunately he exercised the clause and I made some money on it but I never had the opportunity to see the experiment to see whether or not it would work. I asked him and what had happened? And he said, he took the film and showed it to Twentieth Century Fox and based upon that, they picked up the option and they were going to do a bigger film. I said what are you going to do with the one billion dollar film, Bernd? He said, we’re going to hold it and I’ll probably make more money. We’ll release what is now a hundred million dollar film and when it’s finished, I’ll release the prequel and I’ll probably make more money off the million bucks than I’ll make off the hundred million.

Eric: Roger, you’re known as one of the most time efficient film directors…Can you talk a little bit about your most efficiently made film?

Roger: I wouldn’t pick any one in particular. I would pick a series when I was making films generally on ten day schedules. And if there was any secret to working efficiently it’s in pre-production. I’m a strong strong believer in working everything out as much as you can before shooting. The worst thing in the world you can do whether it’s a small picture or a big picture, the director walks in, walks onto the set the first day and says, “Alright. Now where are we going to put the camera?” The director should have figured this out in advance. I believe in storyboarding or sketching which I did myself. All the shots, I never really sketched all of shots. But I would get about seventy to eighty percent of them and a couple close ups. I didn’t need to sketch that. I knew after I got the masters I was going to take close-ups – knowing that you will never follow your plan exactly. You won’t have time, something will make it impossible, or you’ll get a better idea on the set. But if you have your pre production planning set, you can organize your shooting then improvise around it, change it but you still got that skeleton to work with. And another thing is not to sit around and congratulating everybody on the set after a shot. It’s amazing how much time is spent when you get a shot and someone says that’s a great shot, what did you think of that? And the first thing you know is five minutes have gone by and everyone is discussing the shot. I trained myself to say, cut, print, excellent, very good, whatever, the next shot is over here. And we moved instantly. I took only a few seconds to compliment the actors or something and move to the next shot. There are number of other things, but basically it’s working intelligently and working with preproduction.

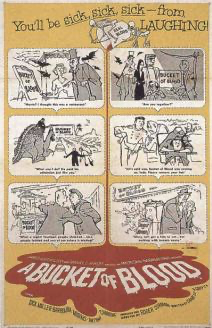

Eric: A Bucket of Blood. I read somewhere that you shot that in one and half days or something…

Roger: I shot A Bucket of Blood in five days. And then I broke my record with Little Shop of Horrors in two days and a night. And Bob Towne who has gone on to be an Academy Award winning writer, director is a good friend of mine, told me to remember that making a picture is not like a track meet, it’s not how fast you go. And I said, you’re right Bob, I’ll never make a picture in two and half days again. And I never did.

Eric: What was Peter Lorre like to work with?

Roger: Peter was great. He had studied with Bertolt Brecht in the Berlin ensemble in the twenties and thirties and he had left Germany because of the Nazi movement in the 1930s. And he was very free and worked in a very improvisational style which I liked very much. And so he would come in vaguely knowing his lines but prepared to improvise and work around it. I had been trained a little bit that way. I had studied with Jeff Corey, one of the best teachers of method technique in Hollywood. And some of his students were Jack Nicholson and a number of other people who have gone on to be very successful. I enjoyed working with Peter because he was also very funny. Particularly in The Raven which was a comedy horror film. I’d say fifty percent of the humor came from Peter’s improvisations.

Eric: Could you relate any stories working with Boris Karloff or Vincent Prince, please?

Roger: There are many stories I may come back to. Somebody mentioned Peter Lorre. On The Raven I worked with all three of them. And they all had different techniques. Boris had been trained in London as a theatrical actor and he came in fully prepared, knowing his lines and prepared to give a performance according to those lines. Peter as I said worked very improvisationally and came in with a general idea of what he was going to do. And it drove Boris crazy. And he came to me he said, Roger, I know what I’m doing. I’m prepared to do it. Peter never gives me the line I’m expecting. And I said, I’ll try to work this out. And I sort of brought it all together. Then Boris became a little more flexible, Peter came a little closer to knowing his lines, and Vincent who understood both the classical techniques and the improvisational was a great help because he was able to work with both of them and sort of bridge the gap. And the net result is they all liked each other. They got along very well and the picture turned out very well. It was one of the first of the horror films that I put comedy. And I have always felt that comedy should be at least some small part of a horror film.

Eric: Is New Concord still doing acquisitions? And if so, what sort of stuff are they looking for?

Roger: We are doing a few of them, fewer of them. We are releasing about, tried to release twenty four pictures a year, two pictures a month in our home video. And we found that we were making only half of them and acquiring half of them. The acquired films were not quite as successful as we hoped so we cut that back a little bit. We are still acquiring films occasionally but not as many as we did before. The ones that seem to work best for us are for better or for worse, the films everybody knows. Horror films work. Science Fiction. Action Adventure. Those three categories plus a few others are the ones that work the best.

Eric: You just said horror/comedy that you liked, but is horror/comedy still a viable commodity?

Roger: Yes, and there you get into a matter of judgment as to with you would say that the raven was a horror with some comedy and Little Shop of Horror is comedy with some horror. Commercially what works best is to emphasize the horror and have just a little bit of comedy to work with it. As soon as I say that, somebody will do the exactly opposite and have a tremendous hit.

Eric: Generally, how do you decide what to make?

Roger: Generally, it’s my idea but my staff, most of them have been with me for a number of years. We work together. We understand well at least we think we understand what works in the marketplace and we put that together with what we ourselves want to do. For instance, I did a number of westerns before I started. We hadn’t done a western in years and about four or five years ago, just because I wanted to do a western, it had nothing to do with the marketplace. I thought it would be interesting. I did a picture called Cheyenne Warrior and it was very successful for us. And we’ll probably be doing another western this upcoming year. So it’s our own personal feelings with an eye on the market.

Eric: Were there any other bands under consideration for Rock and Roll High School or were the Ramones your first choice?

Roger: The Ramones were the first choice from the beginning. We wanted them. They liked the scripted. Allan Arkush who directed it had a contact with them. And I thought they were great.

Eric: I just wanna say I’m a huge fan. And I was wondering what differences do you see in horror movies today as compared to when you were working for AIP?

Roger: There are two differences. One, technically, all of motion picture techniques are far advanced from what we were doing. So technically, they are much more polished and much more effective. The other difference and I think that’s wonderful. The other difference which is not so wonderful is that they are more graphic. We worked more indirectly. We tried to set up a situation, a spirit of suspense, leading to horror. Today they are more likely to chop off someone’s hand. The problem with that is, you chop off somebody’s hand and the next director is going to cut it off from the elbow, the next guy is going to cut him off at the shoulder. And you reach a point of diminishing your return. I prefer to work more indirectly.

Eric: What are your thoughts about Ed Wood?

Roger: I don’t know Ed Wood’s work that much. I’ve actually never seen one of his films. I understand they’re not particularly good. However, you have to give him credit for one thing. He made the films. Those of you who’ve been around Hollywood know how hard it is to raise the money and actually make a film. You have to admire his tenacity, his dedication, that he dedicated his life raising the money to make these films. And he did make the films.

Eric: Do you have any pet projects that you’re still desperate to make?

Roger: Nothing in particular. I have my old projects of Robert E. Lee which I keep thinking I’m going to bring out but probably never will. Beyond that, I don’t have any specific project.