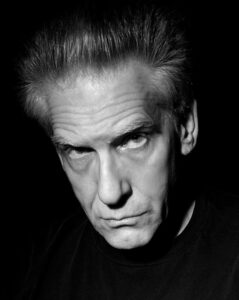

INTERVIEW WITH DAVID CRONENBERG by Mondo2000

I’m not interested in the latest camera development. I’m very anti-techno. I’ve never shot in CinemaScope. I’m not interested. But I can’t understand a director who doesn’t really understand what different lenses do. I’ve got to tell my cameraman what lens I want. He can’t tell me. If you don’t have some technological understanding of why that looks that way, you’ll never understand that it can be different.

I could see what was going on with Stanley Kubrick at a certain point: an obsession with technology. I thought, ‘Why is there so much Steadicam in ‘The Shining ?’ It didn’t surprise me when I heard that the guy had been hired to do one day and stayed for nine months! It was a new toy. In Barry Lyndon it was the emphasis on being able to shoot candlelit scenes by true candlelight, and modifying stills camera lenses for use on a movie camera. But why? The illusion is fine! It’s the illusion I want. The reality is totally irrelevant.

Yet, inevitably, when you do special effects it’s always an invention. It’s always a new experiment, because the context is always different. Even in Dead Ringers I was breaking some new ground in small ways with motion control. Not because I wanted to, but because I had to, and wanted to survive the experience.

I had no influence whatsoever. I don’t mean that in an arrogant way, but in a very tangible way for me. I didn’t feel the hand of someone on my shoulder, like Hitchcock’s on Brian De Palma. There was not one film-maker who was so almost me that I couldn’t get to the real me. An important element in my decision to go into film was because it did come relatively easily. I’m sure that was one of the reasons I wrote ‘Orgy of the Blood Parasites’ (Shivers). It just sprang up. There was some other momentum there, when I was writing for the screen, that wasn’t there in the novel. That was exhilarating. Interestingly, both Crimes of the Future and Stereo were influenced by Ron Mlodzik, a very elegant gay scholar, an intellectual who was studying at Massey College. He played the lead character in both of them. When I showed Stereo in Montreal, after a screening a young man came up to me and started to proposition me. I told him I was flattered that he should want me to go to bed with him because he liked my movie, but I wasn’t gay. He was shocked. He was sure after seeing Stereo that I was. I attributed that to the translation of Ron Mlodzik’s presence in Stereo and Crimes of the Future. How that translates to the other films I’m not sure. It’s still very illuminating about my own sensibility though, simply because I chose to use Rona’s lead player in those films. How directly that connects with my own sexuality or not, it certainly connects very directly to my aesthetic sense of his space, and his medieval gay sensibility, which I like a lot. His Catholicism was very medieval, and so was his sense of style.

I’m not particularly insecure or paranoid, but I always thought I would much more likely be put in jail for my art than for my Jewishness. A friend who saw Videodrome said he really liked it and added, ‘You know, someday they’re going to lock you up,’ and walked away. That did not help. I suppose underneath I always had a feeling that my existence as a member of standing of the community was in grave jeopardy for whatever reason. It’s as though society had suddenly discovered what I really am, what is really going on inside, and wants to destroy it. My role in Stereo was as Dr Luther String fellow, the absentee scientist who actually set up the experiment, because in a sense, I had set up an experiment. In Crimes of the Future I am Antoine Rouge, the absentee mentor who has died and who is reincarnated as a little girl.

One of the things you want to do with any kind of art is to find out what you’re thinking about, what is important to you, what disturbs you. Some people go to confession or talk to close friends on the phone to do the same thing. And of course, your dreams are important. I’ve never approached mine in any methodological or psychoanalytic way, but I recognize that they’re interesting- a version of my own reality. I have to pay attention to that. That’s another way to let yourself know what you’re thinking about. You have to subvert your psyche sometimes to know what’s really going on.

I often wonder what it’s like to be a cell in a body. Just one cell in skin or in a brain or an eye. What is the experience of that cell? It has an independent existence, and yet it seems to be part of something that doesn’t depend on it, and that has an existence quite separate from it. When you think of colonies of ants or bees, they aren’t physically joined the way an organism made up of cells is, but it’s the same thing. They have an independent existence, an independent history. But they are part of a whole that is composed of them. That’s what fascinates me about institutions. An institution is really like an organism, a multi-celled animal in which the people are the cells. The very word ‘corporation’ means body. An incorporation of people into one body. That’s how the Romans thought of it. Five people would incorporate and become a sixth body, subject to the same laws as they would as individuals. I connect this with the concept of a human body, in which the cells change regularly. They live and die their own lives, and yet the overall flow of the existence of the body as an individual seems to be consistent. How does that work? It’s very mysterious.

People are fascinated by little sections of the CIA, which might be said to develop independent of the body of the CIA. It’s like a tumor or a liver or a spleen that decides it will have its own independent existence. It still needs to share the common blood that flows through all the organs, but the spleen wants to go off and do a few things. It’ll come back. It has to. But it wants to have its own adventures. That’s fascinating to me. I don’t think of it as a threat. It’s only a real threat if all your organs decide to go off in different directions. At a certain point the chaos equals destruction. But at the same time the potential for adventure and creative difference is exciting.

In Crimes of the Future I talk about a world in which there are no women. Men have to absorb the femaleness that is gone from the planet. It can’t just cease to exist because women aren’t around. It starts to bring out their own femaleness more, because that duality and balance is necessary. The ultimate version would be that a man should die and re-emerge as a woman and be completely aware of his former life as a man. In a strange way this would be a very physical fusion of those two halves of himself. That’s what Crimes of the Future is about. Ivan Reitman once told me it could have been a great commercial success if I’d done the movie straight.

William Burroughs doesn’t just say that men and women are different species, he says they’re different species with different wills and purposes. That’s where you arrive at the struggle between the sexes. I think Burroughs really touches a nerve there. The attempt to make men and women not different- little girls and boys are exactly the same, it’s only social pressure, influence and environmental factors tha t makes them go separate ways- just doesn’t work. Anyone who has kids knows that. There is a femaleness and a maleness. We each partake of both in different proportions. But Burroughs is talking about something else: will and purpose.

If you think of a female will, a universal will, and a male will and purpose in life, that’s beyond the bisexual question. A man can be bisexual, but he’s still a man. The same for a woman. They still have different wills that knock against each other, are perhaps in conflict. If we inhabited different planets, we would see the female planet go entirely one way and the male another. Maybe that’s why we’re on the same planet, because either extreme might be worse. I think Burrough’s comments are illuminating. Maybe they’re a bit too cosmic to deal with in daily life, but you hear it reflected in all the hideous cliches of songs: ‘you can’t live with ’em, and you can’t live without ’em.’

Burroughs was fascinated when I told him about a species of butterfly where the male and female are so different it took forty years before lepidopterists realized. They couldn’t find the male of one species and the female of another. But they were the same species. One was huge and brightly colored and the other was tiny and black. They didn’t look like they belonged together. When Burroughs talks about men and women being different species, it does have some resonance in other forms of life. But there are also hermaphrodite versions of this butterfly. They are totally bizarre. One half is huge and bright and the other half- split right sown the middle of the body- is small and dark. I can’t imagine it being able to fly. There’s no balance whatsoever.

I don’t think of my films as being radical. They’re often received that way, or are perceived with horror of a different kind by censors and by people who feel they must protect the common will. Because of that I look at them and say, ‘I suppose if I were in their shoes, and my understanding of human endeavor were theirs, then these are radical.’ But I don’t think somebody in a country that banned one of my films would say it was because the film was politically dangerous. I don’t think ‘political’ would be the right word in this context. I think it’s because of the imagery, not the philosophical suggestions behind the imagery. It’s the imagery that strikes them first, and then the general disturbing quality of the films.

If it were just a question a mutilating bodies the way that hack-and-slash movies often do, I wouldn’t find extreme imagery interesting. People often say to me, ‘Why don’t you do it the way Hitchcock did and just suggest things?’ First of all I say, ‘Have you seen Frenzy ?’, which has a couple of very nasty scenes. The man did them- he wanted to, no one was forcing him. I think that Hitchcock’s reticence to show stuff had more to do with the temper and censorship of the times than it did his own demons. I have to show things because I’m showing things that people could not imagine. If I had done them off-screen, they would not exist. If you’re talking about shooting someone, or cutting throats, you could do that off-screen and the audience would have some idea of what was going on. But if you imagine Max Renn in Videodrome and the slit in his stomach. If I’d done that off-screen, what would the audience think was going on? It simply wouldn’t work. I’m presenting audiences with imagery and with possibilities that have to be shown. There is no other way to do it. It’s not done for shock value. I haven’t made a single film that hasn’t surprised me in terms of audience response; they have been moved, shocked or touched by things that I thought wouldn’t nudge them one inch. For me, it’s really a question of conceptual imagery. It’s not just ‘Let’s show someone killing a pig on screen and we’ll get a good reaction.’ You would.

So what?

I don’t know where these extreme images come from. It seems very straightforward and natural and obvious to me as it happens. Often they come from the philosophical imperative of a narrative and therefore lead me to certain things that are demanded by the film. I don’t impose them. The film or the script itself demands a certain image, a certain moment in the film, dramatically. And it emerges. It’s like the philosophy of Emergent Evolution, which says that certain unpredictable peaks emerge from the natural flow of things and carry you forward to another stage. I guess each film has its own version of Emergent Evolution. It’s just like plugging into a wall socket. You look around for the plug point and, when you find it, the electricity is there- assuming that the powerhouse is still working. That’s as close to describing the process as I can get.

The lead actress, Sue Helen Petrie, had been in a couple of the Cinepix porno films. In fact, she was in almost every Canadian film being made then. She was very voluptuous but very pretty, and not a bad actress. Funny and very bright. We’re on set and we’re doing this scene, and she has to cry. She really has to cry a lot in the movie because her husband is weird right from the start. She says, ‘David, I’ve got a confession. I can’t cry on screen. I’ve never been able to do it.’ I said, ‘You’ve got to!’ She says, ‘That’s why I wanted to do this role- to show that I can cry. But I can’t.’ I said, ‘Oh my God, what are we going to do now?’ So she says, ‘I’m going to grate onions and put them in my eyes, and then you’re going to slap me across the face, and then I’ll go in front of the cameras and do it.’ She wasn’t kidding; this was another kind of desperation I was having to deal with.

So I say to the crew, ‘OK, you’re going to roll and we’re not going to be on set, and then Sue’s going to run in. So just keep rolling.’ We go around the corner of the kitchen (we were shooting in a very small apartment), and she rubs the onions in her eyes. It doesn’t look like she’s crying. She said, ‘Hit me,’ so I gave her a little tap. ‘That’s not hard enough, you’ve really got to hit me.’ So I hit her, really hard. then she said, ‘OK, now do it ten more times.’ So, five on each cheek. My hands were burning. She shrieks. Shriek, whack, whack, shriek. Then she ran out and we shot immediately. Then Barbara Steele arrives, and the first scene she has to do with Sue is when she gives her a parasite kiss. So it’s pretty tricky; low-budget stuff throws you into that because you have no time for niceties. So Barbara is sitting there, and everybody on the crew is now completely blast about our technique for making Sue cry. The make-up lady comes to me and says, ‘She’s on the verge of bruising now and I won’t be able to cover it. You better take that into consideration.’ But it’s business as usual. We roll the camera. Barbara’s all ready, but I don’t say ‘Action.’ Sue and I go into the kitchen. Barbara’s wondering what the fuck’s going on. So it’s smack, smack, smack, shriek, shriek, shriek. Sue comes out sobbing. Great. Barbara is horrified; there’s a look of total shock and anger on her face. I say,’ Action, action. Do it, do it!’

When it’s ‘Cut’, Barbara stands up (she’s real big, and she was in high heels) and literally grabs me by the lapels and lifts me up. She says,’ You bastard! I’ve worked with some of the best directors in the world. I’ve worked with Fellini. I’ve never, in my life, seen a director treat an actress like that. You bastard!’ She was going to punch me out. I said, ‘No, Barbara, don’t hit me. She made me. I hate doing it. I’m afraid to do take two_’ ‘Really?’ she says. ‘Yes, really.’ Barbara lets me go. ‘How hard were you hitting her?’ she asks, ‘show me.’ She holds out her forearm and I hit it hard. ‘That hard?’ ‘Yes,’ I say. ‘Hmm,’ says Barbara. A pause, and then her eyes fix on me. ‘Do I have any scenes where I cry?’ That was my introduction to the world of actresses. People who see Shivers and think that I didn’t deal with acting and actors are completely wrong. Each of my films has a little demon in the corner that you don’t see, but it’s there. The demon in Shivers is that people vicariously enjoy the scenes where guys kick down doors and do whatever they want to the people inside. They love the scenes where people are running, screaming, naked through the halls. But they might just hate themselves for liking them. This is no new process; it’s obvious that there is a vicarious thrill involved in seeing the forbidden.

Rench critics really saw Shivers as being an attack on the bourgeois life, and bourgeois ideas of morality and sexuality. They sensed the glee with which we were tearing them apart. Living on Nuns’ Island we all wanted to rip that place apart and run, naked, screaming through the halls.

The standard way of looking at Shivers is as a tragedy, but there’s a paradox in it that also extends to the way society looks at me. Here’s a man who walks around and is sweet: he likes people, he’s warm, friendly, articulate and he makes these horrible, diseased, grotesque, disgusting movies. Now, what’s real? Those two things are both real for the person standing outside. For me, those two parts of myself are inextricably bound together. The reason I’m secure is because I’m crazy. The reason I’m stable is because I’m nuts. It’s palpable to me.

At the beginning of my career I encouraged labels like ‘the reigning king of schlock horror.’ It was a defense. To say that what you do is in some way artistic leaves you vulnerable. Andy Warhol stood on that defense himself. He said, ‘Oh yeah, my stuff is trash. No question about it.’ It’s very hard for people to attack you when you say that. Plus the fact that my acceptance of that crown connected me with AIP and Roger Corman, which wasn’t such a bad thing.

Why should I be beaten over the head by what was written about me in The American Nightmare. That Robin Wood says is ‘these are good film-makers who are on the side of progressiveness, and these are bad film-makers who are reactionary.’ I don’t think that is what art’s about, or what criticism is about. I don’t think that films have to be positive or uplifting to be valid experiences. A film can be depressing and still be exhilarating. The critics I have admired the most are a lot less schematically inclined because I don’t base my life’s value and work’s value in any ideology. There is a very strident moral imperative being broadcast from Robin’s work that is really saying that, despite the fact this piece of film by Larry Cohen is awful, it is admirable and should be seen because it proposes what I think it right for human beings to do in society. Now that is very twisted.

Why do actors love death scenes? Partly because they know the scene’s going to get them some attention. But part of it is mystery over death; to be able to die, come back to life, and refine it. ‘Let me try that again.’ They’re trying out what’s aesthetically and philosophically pleasing. Same for me. ‘Here’s Martin Sheen committing suicide in The Dead Zone. Should he put a gun in his mouth? No. ClichŽd. How about under the chin? He’s a guy who would go out with his chin up.’ You can’t help thinking, when you hear the gun click, ‘Would I have the guts to do that?’ You’re deciding the moment and style of your death. I thought at the time it was a defeat when Hemingway shot himself. Since then I’ve come to feel it was a very courageous act. He said the only things that meant anything to him were fucking, fishing and writing, and he couldn’t do any of them worth a damn any more. He lived by his word. This sounds very dreary and serious and very involved. Of course, it’s not like that at all. It’s much more like play. That’s really the way I think of film. It’s the adult version of tigers’ play.

I don’t think that the flesh is necessarily treacherous, evil, bad. It is cantankerous, and it is independent. The idea of independence is the key. It really is like colonialism. The colonies suddenly decide that they can and should exist with their own personality and should detach from the control of the mother country. At first the colony is perceived as being treacherous. It’s a betrayal. Ultimately, it can be seen as the separation of a partner that could be very valuable as an equal rather than as something you dominate. I think that the flesh in my films is like that. I notice that my characters talk about the flesh undergoin revolution at times. I think to myself: ‘That’s what it is: the independence of the body, relative to the mind, and the difficulty of the mind accepting what that revolution might entail.’

The most accessible version of the ‘New Flesh’ in Videodrome would-be that you can actually change what it means to be a human being in a physical way. We’ve certainly changed in a psychological way since the beginning of mankind. In fact, we have changed in a physical way as well. We are physically different from our forefathers, partly because of what we take into our bodies, and partly because of things like glasses and surgery. But there is a further step that could happen, which would be that you could grow another arm, that you could actually physically change the way you look-mutate.

Human beings could swap sexual organs, or do without sexual organs per se , for procreation. We’re free to develop different kinds of organs that would give pleasure, and that have nothing to do with sex. The distinction between male and female would diminish, and perhaps we would become less polarized and more integrated creatures. I’m not talking about transsexual operations. I’m talking about the possibility that human beings would be able to physically mutate at will, even if it took five years to complete that mutation. Sheer force of will would allow you to change your physical self.

To understand physical process on earth requires a revision of the theory that we’re all God’s creatures- all that Victorian sentiment. It should certainly be extended to encompass disease, virus and bacteria. Why not? A virus is only doing its job. It’s trying to live its life. The fact that it’s destroying you by doing so is not its fault. It’s about trying to understand interrelationships among organisms, even those we perceive as disease. To understand it from the disease’s point of view, it’s just a matter of life. It has nothing to do with disease. I think most diseases would be very shocked to be considered diseases at all. It’s a very negative connotation. For them, it’s very positive when they take over your body and destroy you. It’s a triumph. It’s all part of trying to reverse the normal understanding of what goes on physically, psychologically and biologically to us. The characters in Shivers experience horror because they are still standard, straightforward members of the middle-class high-rise generation. I identify with them after they’re infected. I identify with the parasites, basically. Of course they’re going to react with horror on a conscious level. They’re bound to resist. They’re going to be dragged kicking and screaming into this new experience. But, underneath, there is something else, and that’s what we see at the end of the film. They look b eautiful at the end. They don’t look diseased or awful.

Why not look at the process of ageing and dying, for example, as a transformation? This is what I did in The Fly. It’s necessary to be tough though. You look at it and it’s ugly, it’s nasty , it’s not pretty. It’s very hard to alter our aesthetic sense to accommodate ageing, never mind disease. We say, ‘That’s a fine-looking old man; sure he smells a bit, and he’s got funny patches on his face.’ But we do that. There is an impulse to try and accommodate ageing into our aesthetic. You might do the same for disease: ‘That’s a fine, cancer-ridden young man.’ It’s hard, and you might say ‘why bother?’ Well, because the man still exists. He has to look at himself.

That’s why it seems very natural for me to be sympathetic to disease. It doesn’t mean that I want to get any. But that’s one of the reasons I try to deal with that, because I know that it’s inevitable that I will got some. We could talk about the tobacco mosaic virus but that wouldn’t interest us much, not being tobacco plants ourselves. Naturally we’re interested in human diseases. But how does the disease perceive us? That illuminates what we are.

It was an odd movie. The crew was really freaked out by it; most of them people I’d worked with many times. We had some ladies come in and take their clothes off, then we’d chain them to the Videodrome wall and beat them – not for real. One of two of them quite loved it. Most of them were extras, and had never had this kind of attention. But the weirdness of it actually excited a couple of them. One kept reappearing on set, very made-up, very dressed, and just floated around. It was strange; she was someone who’d been strangled and beaten in the scene. So it was undeniably freaky being on that set. It makes sense that it was; it was supposed to be.

I had to make speeches to the crew every once in a while, because at a certain point we were in disarray. I was indecisive at certain junctures as we got closer to the end. We would set up in a place to shoot and then I’d take it apart and go somewhere else. I was feeling my way through a difficult film. Despite the fact that I talk about liking to have a script together, it’s not because I think that means you’ve solved every problem or understand your film. I was beginning to understand more of what was going on in the movie, and that what I originally thought would work wasn’t going to. At one point on the Videodrome chamber set, I actually told the crew what was going on and what I was thinking, to reassure them things were in hand. They were wondering if I was falling apart, or under pressure because of something they didn’t know about. I suppose the immediate thing crews think of is ‘Is this picture going to be cancelled tomorrow? Am I going to be out of work?’

A film like Videodrome , which deals specifically with sadomasochism, violence and torture, is naturally going to have a lot of nervous systems on edge. There was a woman politician in Canada who had pickets out on the streets of Ottawa. They finally got the picture removed from a theatre there because the owner just didn’t want the hassle. That’s fine. That’s his right. But this woman was a politician, connected with a certain party in Canada, and had many particular axes to grind.

I’ve talked about admiring Naked Lunch One of the barriers to my being totally 100 percent with William Burroughs is that Burroughs’s general sexuality is homosexual. It’s very obvious in what he writes that his dark fantasies happen to be sodomizing young boys as they’re hanging. I can actually relate to that to quite an extent. I really understand what’s going on. But if I were to fantasize something similar, it would be more like the parasite coming up the drain, and it would be attacking a woman, not a man. To say that’s sexist is politicizing something that is not political. It’s sexual, not sexist-that’s just my sexual orientation. I have no reason to think that I have to give equal time to all sexual fantasies whether they’re my own or not. Let those people make their own movies- leave me alone to make mine. I feel censored in a strange way. I feel that meanings are being twisted and imposed on me. And more than meanings- value judgments.

As a creator of characters, I believe I have the freedom to create character who is not meant to represent all characters. I can create a woman as a character who does not represent all women. If I depict a character as a middle-class dumbo, why does this have to mean that I think all women are middle-class dumbos? There are some women out there who are. Why can they not be characters in my film if I show Debby Harry as a character who burns her breast with a cigarette, does that mean that I’m suggesting that all women want to burn their breasts with cigarettes? That’s juvenile. To give guidelines to the kind of characters you can create, and the kind of acts they can do that’s obscene, a Kafka hell.

It’s very difficult to divine what’s unconscious and what’s conscious, but if you were to find by analyzing my films, for example, that I’m afraid of women, unconsciously that is, I would say, ‘OK, so what? What’s wrong with that?’ If I am an example of the North American male, and my films are showing that I’m afraid of women, then that’s something which could perhaps be discussed, perhaps even decried. But where do you really go from there?

I would never censor myself. To censor myself, to censor my fantasies, to censor my unconscious would devalue myself as a film-maker. It’s like telling a surrealist not to dream. The way I portray women is much more complex than any ideological approach is going to uncover. The advertisement says that the image of a woman sitting on top of the car in a bathing suit is what a woman should aspire to. This is more insidious. A twelve-year-old girl who sees Videodrome might be very disturbed because she is attracted and repelled by the sexuality- an image of a woman burning herself springs to mind- and by the imagery. But that’s different. There’s no clear message in the film that a twelve-year-old would absorb about how she is to behave when she is mature. that’s not the purpose of art- to tell us how we should live.

To me politics does not mean sexual politics. Politics has to do with power struggles, and parties and revolutions. People use the term sexual revolution in a metaphorical way. It’s a semantic thing.

I remember being shocked to see black ladies coming with their two-year-old kids, because it was a free movie and they didn’t have a babysitter. One baby screamed all the way through. I realized that I was in trouble. They saw the movie; it had no music and no temporary track- I didn’t know about temporary tracks. So there were all these audio holes in the movie, which is disturbing to people who don’t know how movies are made. Complete disaster. I don’t know if there was one card that said anything nice. Basically it was’ You’re fucked.’ But everyone was very sweet. It was ‘How can we help you make this better? Let’s figure out what went wrong.’ Tom Mount was very blunt: ‘This is terrible and bad.’ But he never said the picture was lost. And with all these cards on the floor: ‘Listen to this one- “I hated your fucking film.”‘ It was excruciating. In a way, what you’re asking for is the judgment of strangers when you make art of any kind. You’re asking them to relate and respond to it. But the cards are brutal.

When I had to deal with the T oronto Censor Board over The Broad, the experience was so unexpectedly personal and intimate, it really shocked me; pain, anguish, the sense of humiliation, degradation, violation. Now I do have a conditioned reflex! I can only explain the feeling by analogy. You send your beautiful kid to school and he comes back with one hand missing. Just a bandaged stump. You phone the school and they say that they really thought, all things considered, the child would be more socially acceptable without that hand, which was a rather naughty hand. Everyone was better off with it removed. It was for everyone’s good. That’s exactly how it felt tome.

Censors tend to do what only psychotics do: they confuse reality with illusion. People worry about the effects on children of two thousand acts of murder on TV every half hour. You have to point out that they have seen a representation of murder. They have not seen murder. It’s the real stumbling-block.

Charles Manson found a message in a Beatles song that told him what he must do and why he must kill. Suppressing everything one might think of as potentially dangerous, explosive or provocative would not prevent a true psychotic from finding something that will trigger his own particular psychosis. For those of us who are normal, and who understand the difference between reality and fantasy, play, illusion-as most children most readily do- there is enough distance and balance. It’s innate.

Censors don’t understand how human beings work, and they don’t understand the creative process. They don’t even understand the social function of art and expression through art. You might say they don’t have to and you could be right. If you believe that censorships a noble office, then you don’t have to understand anything. You just have to understand censorship.

It becomes complex when it gets mixed up with the women’s movement. You find great splits there between those who think censorship is necessary and those who still believe in total free expression. An image of a man whipping a woman, for instance. It must come out of a film, whether the movie is set up in such a way that the audience understands this is just play between two lovers been together for forty years and have twenty kids. That wouldn’t matter. The image has to go. So censors become image police: they don’t care what the context of the image is; it’s only the image itself.

The belief is that an image can kill. Literally. It’s like Scanners: if thoughts can kill, images can kill. So the very suggestion of sadomasochism, for instance, will somehow trigger off masses of psychotics out there to do things they would never have done had they not been exposed to that image. That’s why film classification, as opposed to censorship, is legitimate; when it’s a suggestion rather than a law. But then, no one is particularly more qualified to be a classifier than anyone else, which is the problem with censorship. How can someone who is my age, my contemporary, see a film and say that I cannot see the film? I don’t understand that.

What I love about guys like Max Renn (Videodrome ) and Seth Brundle (The Fly) is that they cannot turn the mind off; and the mind undercuts, interprets, puts into context. To allow themselves to go totally into the emotional reality of what’s happening to them is to be destroyed completely. They’re still trying to salvage something out of the situation: ‘Maybe this isn’t a disease at all. Maybe it’s a transformation.’ So I have my reasons for having my characters articulate a lot. It seems real to me. Characters who will not allow themselves to get bathetic. Seth Brundle has built his whole career, life and understanding of the world on cerebration and the thought process. He cannot totally let go of it. He has to get drunk to get jealous, to talk to the ape.

A mainstream movie is on that isn’t going to rattle too many cages, is not going to shake people up, push them too far or muscle them around. It’s not going to depress them. That’s why I don’t think that The Fly is mainstream. No horror film is truly mainstream. When people say, “Great, another Cronenberg movie! Let’s take everybody and have popcorn’- then I’ll know I’m mainstream.

One of our touchstones for reality is our bodies. And yet they too are by definition ephemeral. So to whatever degree we center our reality-and our understanding of reality- in our bodies, we are surrendering that sense of reality to our bodies’ ephemerality. That’s maybe a connection between Naked Lunch, Dead Ringers and Videodrome. By affecting the body- whether it’s with TV, drugs (invented or otherwise)- you alter your reality. Maybe that’s an advance. I don’t know if I’m evolving at all in terms of the struggle.

Gynecologic is such a beautiful metaphor for the mind/body split. Here it is: the mind of men- or women- trying to understand sexual organs. I make my twins as kids extremely cerebral and analytical. They want to understand femaleness in a clinical way by dissection and analysis, not by experience, emotion or intuition. ‘Can we dissect out the essence of femaleness? We’re afraid of the emotional immediacy of womanness, but we’re drawn to it. How can we come to terms with it? Let’s dissect it.’

People who find gynecologic icky say, ‘I don’t find sex icky.’ They’ve never gone into why. Men who put their fingers up their girlfriends can turn around and say the concept of gynecology is disgusting. What are they talking about? That’s one of the things I wanted to look at. What makes gynecology icky for people is the formality of it. The clinical sterility, the fact that it’s a stranger. The woman spaying the gynecologist let’s say it’s a man- and. allowing him to have intimate knowledge of her sexual organs, which are normally reserved for lovers and husbands. Everyone agrees to suppress any element of eroticism, emotion, passion, intimacy. There’s not a gynecologist in the world who would tell you he’s been intimate with eight hundred thousand women.

The other reason gynecology weird men out is that they are jealous. Their wife is known better, not just physically because, yes, you could look up there yourself with a flashlight. The gynecologists understanding of what it all does and how it all works is greater than yours. And he does it all the time. He can compare your wife with other women: structure- does it look pre-cancerous?- all this stuff. It’s his knowing stuff that you can never know. I don’t want to discuss whether I’ve looked up my wife with a flashlight or not, but absolutely I wouldn’t be afraid if I needed to. Neither would she. But it’s something else. It’s a very potent metaphor, such a perfect core to discuss all this stuff.

In a crude sense, it’s certainly the least macho movie I’ve done: there’re no guns, no cars. Scanners was very masculine by comparison. Even The Fly was machinery-dominated. In Dead Ringers the machinery is the gynecological instruments. They’re very menacing on screen, but actually rather effete. The Dead Zone had a lot of femaleness in it, and not just because it’s more emotional. But it’s too simplistic to say that when a movie’s emotionally right out there it’s female and when it’s repressed it’s male.

In Dead Ringers the truth, anticipated by Beverly’s parents- or whoever named him- was that he was the female part of the yin/yang whole. Elliot and Beverly are a couple, not complete in themselves. Both the characters have a femaleness in them. The idea that Beverly is the wife of the couple is unacceptable to him. He can’t accept that they are a couple. El liot has fucked more women, has a greater facility with the superficialities of everything, with the superficialities of sex. But in terms of ever establishing an emotional rapport with women, Elliot is totally unsuccessful. Beverly is successful, but he doesn’t see this success as a positive thing. He sees that as another part of his weakness. He’s a part of his brother’s view of society and has great difficulty accepting his own version. He’s been colonized; he’s bought the imperialist’s line about what is beautiful, proper and correct. He has a lot of trouble hearing his own voice.

Venereal disease is very pro-sex, because no sex, no venereal disease. I know that some people think this is disgusting stuff, but in Shivers I was saying, ‘I love sex, but I love sex as a venereal disease. I am syphilis. I am enthusiastic about it in a very different way from you, and I’m going to make a movie about it.’ It’s trying to turn things upside down. Critics often think I’m disapproving of every possible kind of sex. Not at all. With Shivers I’m a venereal disease having the greatest time of my life, and encouraging everybody to get into it. To take a venereal disease’s point of view might be considered demonic, depending on who you are. In a way, Robert Fulford’s attack on me at the time is more understandable; he was a good bourgeois, responding with horror to everything I did. He would not take the disease’s point of view, not even for ninety minutes.

As an artist, one is not a citizen of society. An artist is bound to explore every aspect of human experience, the darkest corners – not necessarily — but if that is where one is led, that’s where one must go. You cannot worry about what the structure of your own particular segment of society considers bad behavior, good behavior; good exploration, bad exploration. So, at the time you’re being an artist, you’re not a citizen. You have, in fact, no social responsibility whatsoever.

If someone says, ‘Now you must be the citizen and step back to see what happens, examine why you have an impulse to create and show these things, that puts me in a different position. I’m no longer being an artist; I’m being an analyst of the act itself. There are many artists who don’t feel the need to examine the process, or who fear that if they do, it will go away or change.

Nabokov said that and nobody threw rocks at him. I could say in the same breath that I am a citizen and I do have social responsibilities, and I do take that seriously. But as an artist the responsibility is to allow yourself complete freedom. That’s your function, what you’re there for. Society and art exist uneasily together; that’s always been the case. If art is anti-repression, then art and civilization were not meant for each other. You don’t have to be a Freudian to see that. The pressure in the unconscious, the voltage, is to be heard, to express. It’s irrepressible. It will come out some way.

When I write, I must not censor my own imagery or connections. I must not worry about what critics will say, what leftists will say, what environmentalists will say. I must ignore all that. If I listen to all these voices I will be paralyzed, because none of this can be resolved. I have to go back to the voice that spoke before all these structures were imposed on it, and let it speak these terrible truths. By being irresponsible I will be responsible.

There are two main problems. One is the scope of it. It really is quite epic. It’s the mother of all epics. It would cost $400-$500 million if you were to film it literally, and of course it would be banned in every country in the world. There would be no culture that could withstand that film. That is what I was faced with: the difficulty any audience would have plugging into it. As a book, you dip into it, you don’t read it from start to finish. It’s like the Bible; it’s a little bit here, a little bit there; cross-references. You find your favorite parts, like the ching. You look in it when you need it, and you find something there.

To make a metaphor in which you compare imagination to disease is to illuminate some aspect of human imagination that perhaps has not been seen or perceived that way before. I think that imagination and creativity are completely natural and also, under certain circumstances, quite dangerous. The fact that they’re dangerous doesn’t mean they are not necessary and should be repressed.

This is something that’s very straightforwardly perceived by tyrants of every kind. The very existence of imagination means that you can posit an existence different from the one you’re living. If you are trying to create a repressive society in which people will submit to whatever you give them, then the very fact of them being able to imagine something else- not necessarily better, just different- is a threat. So even on that very simple level, imagination is dangerous. If you accept, at least to some extent, the Freudian dictum that civilization is repression, then imagination – and unrepressed creativity-is dangerous to civilization. But it’s a complex formula; imagination is also an innate part of civilization. If you destroy it, you might also destroy civilization.

We’ve become very blasŽ in the West about the freedom, the invulnerability of writers. We take it for granted, particularly on the level of physical safety. But look what happened to Salman Rushdie. And now we find that under their dictatorship, Romanians had to register their typewriters as dangerous weapons! They couldn’t own photocopiers. Every year you had to supply two pages of typing using all the keys, so that anything typed on your machine could be traced back to you. That is true fear of the power of the written word.

But even in the West, writing can be perilous. Taking his cue from Jean Genet, Burroughs says that you must allow yourself to create characters and ituations that could be a danger to you in every way. Even physically. He in fact insists that writing be recognized and accepted as a dangerous act. A writer must not be tempted to avoid writing the truth just because he knows that what he creates might come back to haunt him. That’s the nature of the bargain you make with your writing machine.

Copyright © 2000 Mondo.